If you write a book and no one reads it, did you ever really write it?

The book sat on the library shelf for a good few months after she died. I wasn’t here when the original events happened, only when the end came. I had thought to put the book in the coffin but then events intervened.

Lynette was always a little odd, but only a little, not so wildly odd that you needed to worry. I managed her in the last few years she worked here at the library. Lynette wore the same plaid skirt, same olive cardigan and green shirt almost everyday. She had the same box haircut all the time I knew her. All that ever changed was the little pin she used to keep her hair off her face. Sometimes it had a tiny enamel flower on it, sometimes a little cat, sometimes a strawberry or a heart.

Truthfully I should have made her redundant when we got computers but she was compliant, easy to manage. She had the neatest handwriting and she seemed to just be part of the library. Even if I’d have made her redundant she’d still have been here every day.

The story goes that there had been an academic here, a man. Married apparently. He used to come into the library. He was always friendly to Lynette. It was no secret she was infatuated. It wasn’t returned.

There were, apparently, a lot of girls. He had his favourites, one of whom was Jeanette. They flirted a lot, in the library. He would lean in close and she would smile up at him. There were rumours. His wife was a harridan-aren’t they always though? Jeanette was by all accounts young and attractive and now I have seen a photo of her I can see that they looked good together. Too bad for the wife.

Lynette and Jeanette were friends despite Lynette’s feelings for the man. We’ll never know what really happened. They simply disappeared one day-Jeanette and this man. Just sort of ran away together. No one was surprised. Jeanette had a cousin who thought it was out of character but no one bothered with it much. The wife pressed the police but who believes a scorned wife.

There was a lot of gossip but not much else. Lynette never mentioned it.

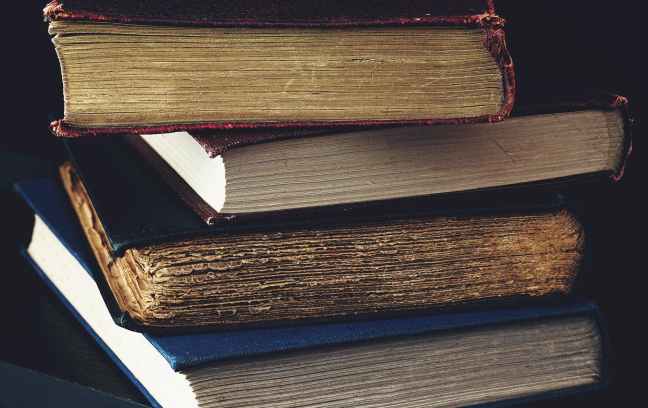

In any event a few months afterwards, the book turned up. In the library. On the shelf. Catalogued and all. No one thought anything of it. It was his last work before he left and ran away, a hardback version, properly bound. It was the only copy we had but we assumed somehow that there were other copies out there.

We should have offered it to his wife, but I wasn’t here then and that didn’t happen. So it sat there and the only person who ever took any notice of it was Lynette. She would take it off the shelf occasionally and look at. Just look at the cover. I once told her she should read it and that’s when it became a kind of joke-if no one reads it has it ever been written. We didn’t do it intentionally but we just kind of made sure that we didn’t ever direct anybody to the book and it just sat there. There was no title printed on the spine and everyone overlooked it.

Then Lynette died. Quite suddenly. And I thought of the book and how it had made us laugh. I thought it would be a nice gesture to place it in her coffin. She had seemed attached to it, a memory of an unrequited love. She had few friends and no family. So I took the book off the shelf.

I sat down to thumb through the pages. It occurred to me after all this time I had no idea what it was even about.

I opened it. And there, where the pages had been cut out neatly to shape a space was a pair of hands bound together, severed off at the wrists and perfectly preserved and a note, in the neatest handwriting.

‘Romance is dead.’